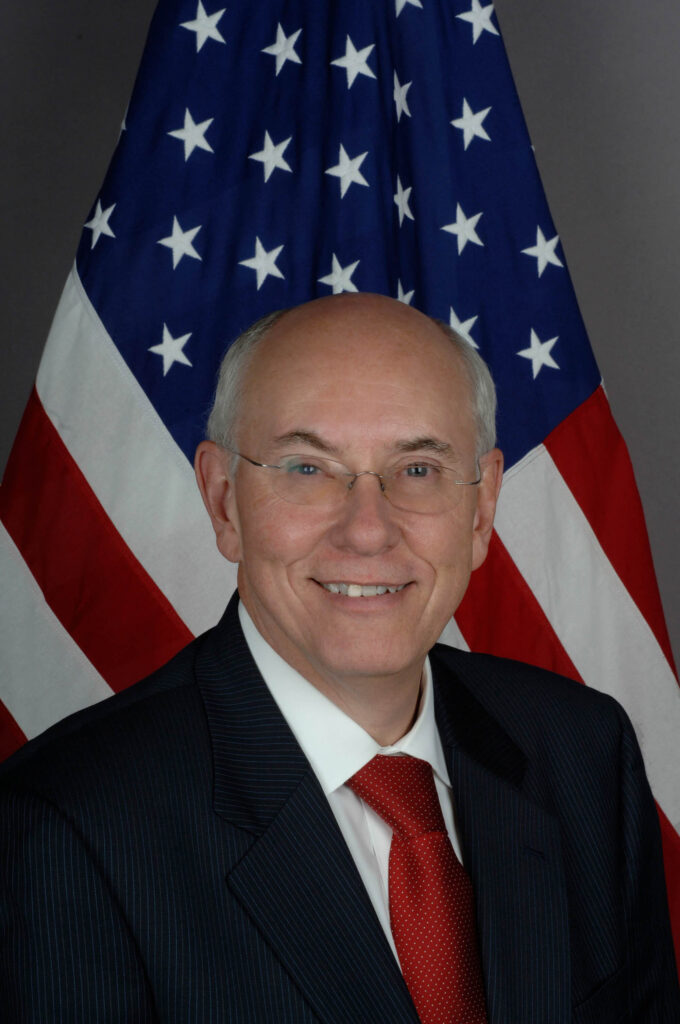

As a senior advisor for International Medical Corps today, William Garvelink is an invaluable “go-to” person for the organization during complex humanitarian emergencies. But throughout his decades-long career with the US government, International Medical Corps was his “go to”—an invaluable NGO partner during the famine in Somalia, the civil war in Angola, genocide in Rwanda and many more conflicts and disasters across the globe. In a mutually beneficial relationship that has literally helped millions of people over the years, Garvelink and International Medical Corps have fought side by side to serve those most in need around the world since first crossing paths.

A kid in his 20s

Garvelink’s own journey started about 100 miles north of Chicago—in Holland, Michigan, the city where he grew up. He attended Calvin College in Grand Rapids, graduate school at the University of Minnesota and worked on his PhD at the University of North Carolina. In 1976, he got hired by Minnesota congressman Don Fraser, who in the 1970s was, according to Garvelink, a “big player” in development, humanitarian assistance and human rights. As one of only two human-rights specialists on the Hill, Garvelink worked as a staff member on the Subcommittee on International Organizations of the Committee on Foreign Affairs of the House of Representatives, where he also encountered political legends like Senator Hubert Humphrey and Senator Edward Kennedy.

“I was a kid out of grad school in his 20s working for these terrific guys,” says Garvelink. “It was such a great experience.”

When Congressman Fraser lost his election in 1979, Garvelink was out of work. Around that time, Michael Hershman, the former chief investigator of the Watergate scandal and later Deputy Inspector General for the US Agency for International Development (USAID), called Garvelink and offered him a job. He lasted for six months in the audit office before switching to USAID’s policy office, which he calls “the greatest thing that ever happened to me.”

He spent five years as a Program Officer in USAID Bolivia and then, upon his return to DC, got a call “out of the blue” from the State Department asking him to work on refugee programs in southern Africa. Two years later, while in Malawi working on the Mozambique refugee crisis, he got another call out of the blue—this one from Julia Taft, the head of the US Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA). Taft said to Garvelink, “I heard you’re an aid guy.” When Garvelink said yes, Taft told him, “Well, then get back here and work for me.”

That call would change his life.

“That changed everything”

Garvelink spent 11 years with OFDA—first as Assistant Director for Response, then as Deputy Director and later as Acting Director. That’s where, in the late 1980s, he first met Nancy Aossey, the new CEO for International Medical Corps. He gave the organization one of its first grants to do work in Honduras and El Salvador, where we were providing healthcare for those displaced by armed conflict in Nicaragua.

In those days, International Medical Corps did not have an office in Washington, DC, so when Aossey would fly in from Los Angeles for meetings, she would camp out in OFDA’s waiting room and use the phones to make calls. Garvelink recounts how she also consistently faxed him memos at home into the wee hours of the night—until he retaliated by faxing her a blank sheet of paper two nights in a row at 2 a.m. She got the hint.

“She was around all the time, and she kind of drove me nuts,” says Garvelink with a laugh. But he came to quickly respect Aossey’s persistence and commitment. Eventually, he let her use a vacant office to make calls and it wasn’t long before he considered her the “go-to person” for OFDA. Though there were a number of much larger humanitarian organizations in those days, Garvelink quickly learned that, when things got really bad during an emergency, he could call Nancy up and—no matter what the disaster was—she would say “yes.”

At the time, as a direct result of actions taken by Garvelink and his boss, Julia Taft, a major shift was taking place in the way that humanitarian relief got delivered in conflict situations. Before about 1988, United Nations agencies and NGOs did not cross national borders into a warzone without permission to provide humanitarian assistance. The official protocol would be for humanitarian organizations to wait until civilians fled the conflict area and crossed an international border, thus becoming refugees. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) would then establish refugee camps in these neighboring countries, and humanitarian organizations would provide the services. “One NGO would do water and sanitation, another would provide food, another would run healthcare and so forth—but strictly within the confines of the camp,” says Garvelink. “And that’s the way it was always done.”

But in 1988, as reports started coming out about brutal fighting in southern Sudan between the government of President Omar al-Bashir and the Sudanese Liberation Movement (SPLM), a few prominent NGOs came to OFDA, to appeal to Garvelink and Taft for help in reaching people displaced within the country.

“They said, ‘People are starving and dying, and we can’t do anything,’” remembers Garvelink. “So Julia and I went to the State Department, which turned us down on the spot, telling us we could not violate Sudan’s national sovereignty.” Still, the horrifying reports of civilians dying kept coming. A month later, the NGOs came back. Garvelink and Taft went back to the State Department and were eventually told by then-Deputy Secretary of State, Larry Eagleburger, “Okay—don’t ask permission, just tell Bashir and the SPLM that you’re going to provide humanitarian assistance.”

According to Garvelink, the State Department “went nuts.” While Eagleburer dealt with the fallout, Garvelink and Taft went to meet with President Bashir in Khartoum. They told him, “We’re going to come into the country to provide assistance to the displaced population. We’re humanitarians. We’re not causing problems. If you want to inspect our cargo, you can.” They then went to the head of the SPLM, John Garang, and told him the same.

“That changed everything,” says Garvelink. “That’s how humanitarian assistance has been provided ever since.”

UNICEF designed a humanitarian assistance plan, called Operation Lifeline Sudan (OLS), and began transporting cargo and relief through Kenya and Ethiopia to those displaced in southern Sudan. OLS continued for 15 years—and International Medical Corps, which has been working in Sudan since 1994, eventually played a big part. “It is to me one of the most remarkable relief efforts the world has ever done, yet nobody pays any attention to it anymore,” says Garvelink. “We were operating in the middle of a warzone, but there were never any peacekeepers involved—it was strictly humanitarian.”

First in line

A couple of years later, Garvelink says International Medical Corps was a “big player” in the response to the drought in Somalia, working in the midst of a violent civil war to get lifesaving healthcare and food assistance to starving civilians. International Medical Corps managed Digfer, the biggest hospital in Mogadishu, and Garvelink would stay at the mission’s house during his visits to the country. He remembers an American nurse whom everyone referred to as “Mother Theresa.” A volunteer with International Medical Corps, she was quiet and shy, and would draw in her diary “all of the crazy things happening in the hospital”—like the time that guerilla fighters showed up at the hospital and held her at gunpoint.

Garvelink is full of stories like this, recounting a time when intrepid humanitarians braved warzones and insane violence to help people in extreme suffering—mammoth efforts that took relentless optimism and ingenuity. He remembers when Aossey set up an air transport service in Somalia to get workers and supplies in and out of Mogadishu, creating an unprecedented model later used by the World Food Program in the Balkans War. No one taught her how to do this, and no NGO had done this before, according to Garvelink—but Aossey figured it out because that was what was required to deliver lifesaving aid.

Around that time, another civil war was breaking out—this time, in Angola between the government and rebel forces led by Jonas Savimbi. Garvelink and Andrew Natsios, then head of OFDA, tried to do the same thing that had been done in Sudan—facilitate talks with both sides to provide aid to everybody in the conflict area on both sides. They recruited Aossey to join them on an assessment in Angola.

“I remember Nancy asking, ‘Why are we flying into Jamba in the middle of night?’” he says. The pilot answered, “They might shoot us down otherwise.” So after arriving in the dead of night, they were taken the next day to an underground bunker, where Savimbi was guarded by dozens of men with machine guns.

As Garvelink, Natsios and Aossey headed down the stairs, Garvelink stepped aside and told her, “Ladies first!” He says she looked at him “like I was crazy,” but she went down the stairs first—leading the way into the bunker of a brutal warlord. What could have been a very dangerous situation turned into “a very cordial meeting,” he remembers. “Nancy was very thoughtful and asked Savimbi questions about what was needed.”

After the meeting, the United Nations worked with OFDA to set up a humanitarian corridor similar to the one used in OLS—and International Medical Corps played a pivotal role, vaccinating hundreds of thousands of children by training community vaccinators and supplying vaccines.

This success was followed by headline disasters, such as the Rwanda genocide, the Balkans conflict, civil war in the Democratic Republic and much more. And over and over, says Garvelink, “International Medical Corps was the first one there—willing to go where no one else would.”

A partner to rely on

Over the many years that their paths intersected, Garvelink got to know Aossey and International Medical Corps well. “We talked a lot, and at some point I said to her, ‘For better or worse, stay focused on the humanitarian stuff,’” he says. He cautioned her against following other NGOs, some of which “try to do everything and end up not doing anything really well.” She did this, he says—and got “really, really good.” Wherever Garvelink found himself in the world for many years to come, International Medical Corps was always there.

“As time went on, I was the USAID director in Eritrea—and International Medical Corps was there,” says Garvelink. “And when I became the ambassador to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, International Medical Corps was there.” From smaller places like Burundi to huge emergencies like the Indonesian tsunami, Garvelink knew could count on International Medical Corps to provide critical assistance when things got tough. “I would call Nancy up for help, and she would say, ‘Our teams are already on the way,” he says. “Throughout my entire career, International Medical Corps always came through—they never said, ‘We can’t do that.’”

Despite his close relationship with the organization, Garvelink did not visit International Medical Corps’ Los Angeles headquarters until after he retired from the government. Aossey eventually talked him into joining the organization in an advisory position, which he continues today as senior advisor to Ky Luu, International Medical Corps’ Chief Operating Officer.

“I’m hardcore fan,” says Garvelink of International Medical Corps. The feeling is mutual.