True love can be a tangled knot of joy and adversity, with life’s graces and hardships binding us together. For emergency responders Emilie Calvello Hynes and Greg Hynes, it was acute human tragedy—the devastating 2010 Haiti earthquake—that brought them together. And for the past 11 years, rushing to the aid of communities devastated by disaster here in the US and around the world—while bridging their families and building a home—they have been each other’s solace in the storm.

Greg, a flight nurse who had volunteered with International Medical Corps in Indonesia after the 2004 tsunami, was in Park City training as an Olympic hopeful when he got a call from International Medical Corps on January 12, 2010, saying that a massive earthquake had devastated the island nation of Haiti. He drove back to Denver, grabbed a bag and got on a plane, arriving in Port-au-Prince roughly 24 hours after the earthquake, which killed an estimated 250,000 Haitians and displaced 5 million more.

When Greg and his small International Medical Corps team arrived, hundreds of bodies were strewn everywhere, with no more places to put the dead. The hospital campus had collapsed, with all of the nursing students and professors in it. “There were very few health professionals—I think there were two surgeons, a couple of nurses and maybe one physician who wasn’t a surgeon,” says Greg. “We got to work immediately and did the very best we could—but it was really dire and austere.”

Emilie was in Baltimore at the time, having just finished her residency at Johns Hopkins. She was the first of her Hopkins colleagues to volunteer, arriving in Port-au-Prince with another International Medical Corps team a few days after the first team arrived. On her first day working in the emergency tent, Greg was cleaning out a wound and wanted to send his patient home with antibiotics. Unsure of which one to prescribe, he approached a woman wearing a piece of duct tape on her chest with “Dr. Emilie” written on it.

“I go up to her and say, ‘Hi, I have a patient over there who I want to send home with an antibiotic—can you help me pick which one?’” Emilie told Greg, “Do what you would normally do,” to which Greg responded, “I’m a nurse.” Greg’s revelation was met with a “horrified” look. Emilie had mistaken Greg, who was doing procedures more typical of a mid-level practitioner, for a doctor. “And then she got very indignant—very, very mad at me,” says Greg, with unmistakable adoration in his voice.

“I gave him a very self-righteous tongue-lashing,” admits Emilie with a sheepish laugh. “I told him he was practicing outside of his scope on a vulnerable population.”

“But I don’t get flustered very easily,” says Greg. “So she gave me my tongue lashing and dressed me down, and I said to her, ‘Okay, so now which antibiotics?’”

“And I told him which ones to prescribe,” says Emilie. “I did tell him that!”

“So yeah—that’s how we first met,” he says with a smile.

Later that night, Emilie checked out the hotel conference room in which much of the International Medical Corps team was sleeping. After seeing the big cracks on the walls, she decided she would rather sleep outside with the Haitians. She dragged her little tent outside and set it up on the driveway. There was one other little tent there: Greg’s. And under a starry island night in the midst of incalculable human suffering, they got to talking.

For several more weeks, Emilie and Greg worked long hours treating Haitians who had various wounds and traumas, and then spent their evenings chatting. Emilie says that, as someone from the east coast, where paramedic flights tend to be very short distance, she was “very humbled” to learn about Greg’s experience as a flight nurse in Colorado, where flights tend to be longer and require more advanced medical skills to keep patients alive. “That set us up for me knowing and trusting Greg, and knowing that he’d be able to function in such environments,” she says.

After returning home to the US, they stayed loosely in touch across 2,000 miles via text and email. Six months later, Emilie volunteered with another organization in Haiti that desperately needed a nurse-educator. She called Greg and asked him to come back to Haiti. He did, and they continued to get to know each other. “There’s this thing that happens in the field, when you’re living in a world that a lot of people don’t understand, and then you meet somebody who can function in that space and who is kind and compassionate,” says Emilie. “We had a longstanding, professional friendship—but we secretly liked each other.”

In 2012, they found themselves once again volunteering together, this time in Patna, India, working on a prehospital trauma system assessment. One day, Emilie wandered into the communal kitchen and told Greg, “I love you.” Greg’s response? “Oh, okay.”

He laughs as he explains that he was “slower to come on board,” namely because of the “other lives” they had to sort out back home: ex-spouses and, in Emilie’s case, two young sons. Following Emilie’s confession, they remained friends for a while with “the occasional hug that lingered a beat too long.” Says Emilie, “We were like totally awkward nerds that stare at each other across the dance floor at the eighth-grade dance and then dance, like, six feet away from each other.”

“In hindsight I was totally in love with her before I admitted it to myself,” says Greg. “And a lot of it was that shared experience—the austerity.” By the end of 2011, nearly two years after they first met, Greg could no longer deny his feelings. “I realized, ‘Ohh—I like her,” says Greg. “I like her a lot.’”

He decided to leave Denver, where he had just sold his house, and work in Maryland to see where things could go with Emilie. Despite not knowing how to sail, he bought a boat in Seattle and drove it across the country. “He put this boat in the Baltimore Harbor and was like, ‘I’m here to figure out whether this is going to work,’” says Emilie, laughing. “And I said, ‘Well, you look awfully committed.’”

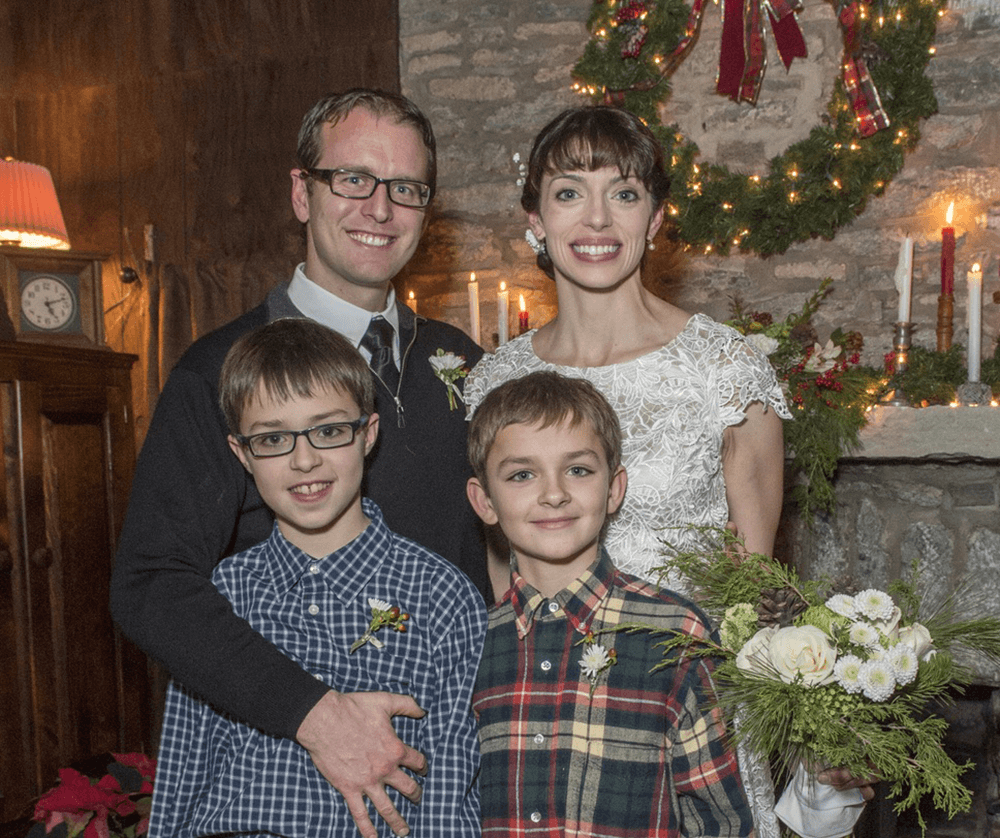

After that, “things got kind of crazy.” Emilie moved to South Africa for some global health work while Greg finished tying up loose ends at home. He eventually joined her and her sons in Africa, and the four of them began moving around the world as a family, including living in the United Arab Emirates for a year, returning to Baltimore for a bit—and finally settling in Colorado. Back home, the couple had a son together, and Greg formally adopted Emilie’s sons, now teenagers, in 2020.

Up until March 2020, the couple continued to volunteer overseas frequently—and then COVID-19 hit, bringing things home in an unprecedented way. Greg points out the irony that, after traveling the world working in disaster zones, his own country began to feel something like that. “A disease outbreak, an overwhelmed healthcare system, political unrest, a contested election, protests and violence in the streets—these are things that we trained people for who wanted to go abroad, and over which we would be advising them to reconsider their trip,” he says.

These days, Emilie directs the Global Emergency Care Initiative in the Department of Emergency Medicine at the University of Colorado, and Greg is a nurse practitioner at urgent-care centers in the area, in addition to his work as a flight nurse, with a number of his transports being critical COVID patients. Being on the frontlines of the pandemic this past year has been trying on both of them, “but again, there’s that benefit of shared experience where we can understand each other’s stress,” says Greg. They also know—all too intimately—how much worse things could be.

“Even during the worst of times here in the US, it’s still significantly better than it is for the majority of the world, which is why we do the work we do,” says Greg. “We appreciate the opportunities, benefits and amazing life that we have, and we ‘fill up our tanks’ here so that we can then go spend it in other places.”

As emergency responders with a passion for working abroad, they make sure to check in with each other’s emotional health often—knowing that the transition coming home can sometimes be harder than the transition leaving. “We make sure to say, ‘Let’s talk about what you saw, let’s talk about how you feel about it,’” says Greg. “And, ‘Let’s make sure this doesn’t stay in a ‘box on the shelf’ that rattles and falls off at the most inopportune time.’ It helps having someone who gets it.”

“We obviously thank International Medical Corps for each other because there’s no way that I would have met Emilie otherwise,” says Greg. On a planet of more than 7 billion people, traversing the globe’s hardest-hit places, they were able to find comfort, stability and a home—in each other. “The adversity we’ve been through has helped us really understand each other, live together more fully and just have more grace with each other as well,” says Greg.

After all, whether we’re emergency responders on the frontlines or not, we all carry invisible scars—and maybe trust, and sometimes even love, comes when we let someone else see them.