Many people in the United States have never even heard of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Very few know that this massive country—roughly two-thirds the size of Europe—endured the deadliest war on any continent since WWII, involving soldiers from eight countries and killing an estimated 5.4 million people between 1998 and 2003. DRC’s humanitarian needs remain enormous today, in large part due to the country’s vastness, complexity and relative impenetrability. More than 6 million children in DRC under the age of 5 suffer from acute malnutrition—and as Ponyo Salumu, a nutrition manager with International Medical Corps, knows all too well, reaching them can be extremely challenging.

Ponyo grew up in DRC and completed medical school in Bukavu in 1994, as some 2 million refugees flooded over the border fleeing genocide in nearby Rwanda. He began his humanitarian-relief career in a Rwandan refugee camp with CARITAS in the eastern part of DRC. There, he met desperate and scared people who had lost everything and witnessed unimaginable horror, and he tried to offer any support he could. Then he watched the same thing happen to his home country, as brutal fighting broke out in 1996 and he, along with everyone who could, fled DRC in search of refuge in nearby countries.

But Ponyo felt a responsibility to his community, and he returned home relatively quickly to participate in nutrition assessments in war-torn areas and to implement lifesaving nutrition programs in the midst of the violence. For the duration of the war, he worked with Action against Hunger in DRC. Though he was able to reach and help many, countless people still died of hunger. Says Ponyo, “It was really hard to get people to come from the outside to do this work in the remote area”—and he was one of the very few on the inside willing to do it.

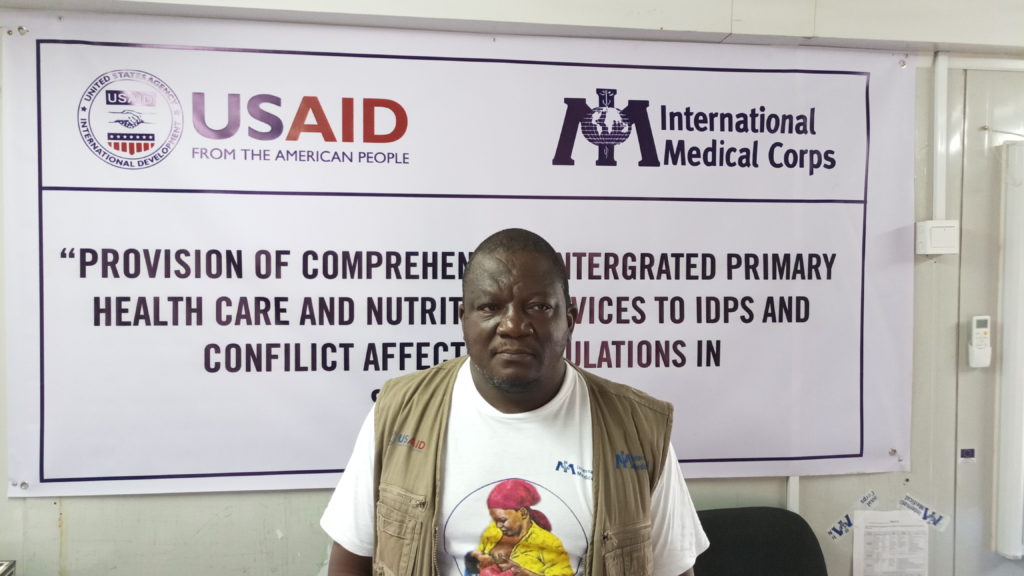

In 2006, Action against Hunger promoted Ponyo, sending him to work in the Central African Republic. After that, he spent the next several years working with various NGOs across Africa, including in Chad, Mali, Burkina Faso and South Sudan. He then joined International Medical Corps in South Sudan in 2015 as a Nutrition Manager, based in Malakal. Today, he spends a lot of time there training local staff on how to measure malnutrition in children, manage community nutrition programs and provide medical treatment for malnourished children under five. He says there has been notable improvement in the country’s internal capabilities, due to the training and collaborative approach of International Medical Corps. “We work as a team with one goal, not as individuals,” he says. “We succeed together.”

It takes a strong team to face the constant challenges posed by insecurity and restriction of movement in South Sudan—challenges that affect both humanitarian workers and those they serve. Still, positive changes are taking place. Ponyo recalls the story of Monday Noah, whose 18-year-old mother was nine months pregnant when she and a number of other internally displaced people sought refuge in Malakal after fleeing fighting in Wau Shilluk. After she gave birth prematurely at a primary health center run by International Medical Corps, Monday Noah was found to be malnourished and suffering from diarrhea. Ponyo and his colleagues treated

Monday Noah and taught his mother how to properly nourish him as he grew—halting his decline and inspiring her to become a lead mother in our Infant and Young Child Feeding program in Malakal. Today, she leads discussions and mobilizes other nursing and pregnant women to participate in our mother-support group sessions, where they learn the benefits of exclusive breastfeeding, complementary feeding and postnatal care.

Monday’s case is one among hundreds of children who receive treatment for malnutrition at International Medical Corps nutrition centers in Malakal. As conflict and displacement continue to destroy livelihoods and food cultivation in the country, the people of South Sudan are experiencing a widespread famine. There, as in DRC, very few people will do the hard work of saving the lives of children and women amidst dangerous and challenging conditions. But Ponyo is willing—and is committed to providing service well into the future.