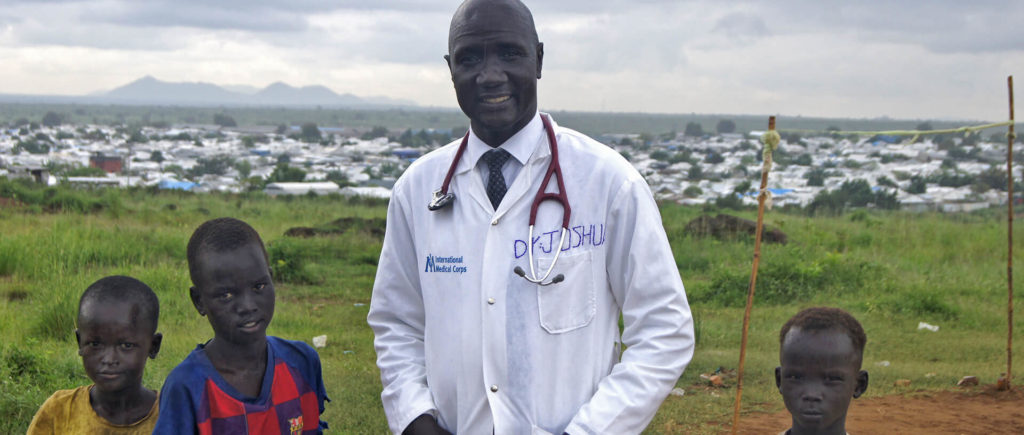

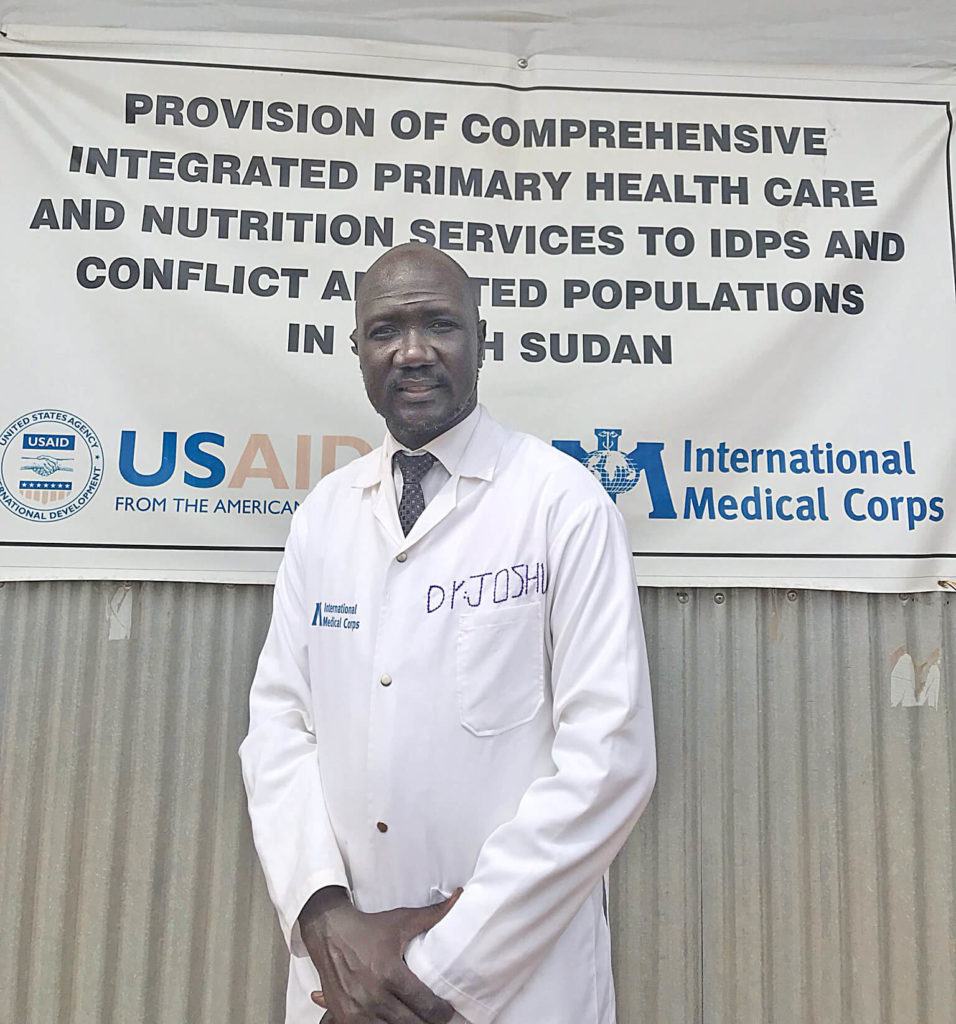

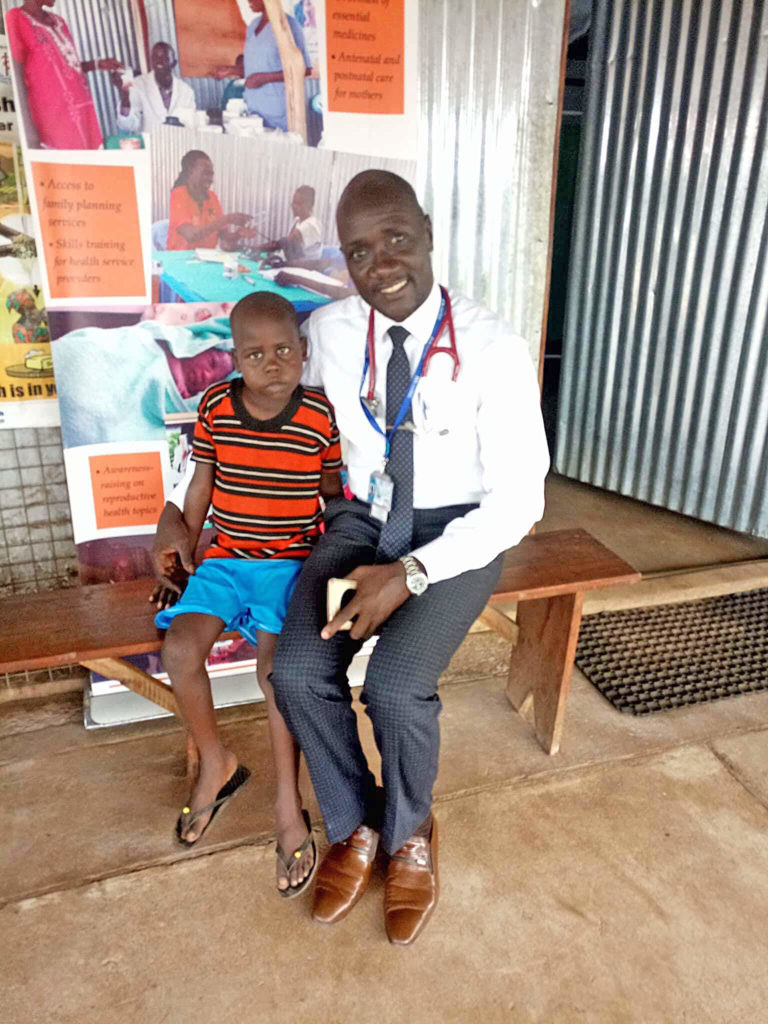

Being a doctor in South Sudan—a conflict-ridden, chronically insecure, abysmally poor country—is one of the most daunting professions on earth. Dr. Joshua Jockjio, a South Sudanese medical professional in charge of International Medical Corps’ health facility in Juba’s “protection of civilians” camp, has faced many challenges over the past four-and-a-half years—including being the only doctor left in the camp to care for wounded fighters and displaced civilians when violence broke out 2016. When asked about the circumstances that he and his colleagues face on a daily basis, he says, with surprising lightheartedness, “We manage.” Then in May, Dr. Jockjio encountered a new challenge: he contracted COVID-19.

He still does not know how he got it. As soon as reports started coming in about the pandemic, International Medical Corps took protective measures to ensure the safety of our staff around the world, including in South Sudan—training them all in infection protection and control, providing personal protective equipment (PPE) and implementing social distancing measures. Dr. Jockjio lives within the camp and never left during the quarantine, so he assumes he contracted the virus from a civilian who traveled to the market, where the first COVID-19 cases started appearing in early April.

In early May, Dr. Jockjio came down with a severe headache. At first, this didn’t seem unusual—he sometimes gets headaches after long, stressful days. But he couldn’t sleep this one off. So he called his colleague and he told him to put on PPE and come over to take a sample. When the test came back positive two days later, Dr. Jockjio’s biggest worry was not his own health, but whether he would transmit the virus to others—particularly his patients with chronic illnesses.

By May 11, Dr. Jockjio had developed a cough, high fever and chills, and our South Sudan team prepared an ambulance to take him to the COVID-19 treatment center. As no curative treatment for the virus currently exists, all of his treatment was supportive: he was given anti-malaria drugs and medication to mitigate his cough and fever, and was told to eat fruit and a balanced diet. “During treatment, I wasn’t scared because there were a lot of people who took care of me and came and checked on me often,” he says. “I got a lot of support from my International Medical Corps colleagues in South Sudan and around the world, and lots of phone calls from my relatives and friends.”

Dr. Jockjio could not be discharged until he had two consecutive negative test results, which finally happened on June 14—more than a month after the ambulance came to get him. He went back to work the very next day. “Coming back to work was very right,” he says. “I had a lot of welcoming from colleagues and the community, who told me how valuable I was to them for taking care of them.”

Across South Sudan, the number of COVID-19 cases is increasing every day, but health facilities have not yet been overwhelmed, as many people are choosing to stay home to heal, according to Dr. Jockjio. Still, with four ventilators for a population of 11 million, it wouldn’t take much to reach a tipping point. International Medical Corps, which recently set up the country’s first and only intensive-care unit, remains vigilant to the pandemic’s threat and is prepared to respond rapidly.

In hopes that the day won’t come when his community is faced with wide-scale tragedy from the virus, Dr. Jockjio remains characteristically positive and grateful. “I would like to send my gratitude to everyone who was concerned for my health from International Medical Corps, the Juba community and my colleagues who have been with me over my entire career,” he says. “I am very healthy and happy now.”

International Medical Corps has been working in South Sudan since the mid-1990s, nearly 20 years before a national referendum in 2011 led the southernmost states of Sudan to become an independent country. Today, amid ongoing violence, we work with the government of South Sudan to strengthen local healthcare capacity in five of the country’s 10 states and deliver health services to nearly half a million South Sudanese. Learn more about our work in South Sudan.