Editor’s Note: International Medical Corps’ Yemen Blog presents a rare view of life on the ground in Yemen, chronicled by our first responders as they battle what is widely acknowledged as one of the world’s worst humanitarian disasters—one fueled by poverty, hunger, disease and a seemingly endless war, now in its seventh year.

The entry below is written by Fayad Al-Derwish, our Senior Officer responsible for water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) programming in Yemen’s southern governorates. By its very nature, the humanitarian work Fayad does draws him to areas where Yemen’s hardship, hunger and human suffering are at their worst—and the war is never far away. In this entry, Fayad relates his own deeply personal journey as a child growing up with signs of autism and explores the fate of those Yemeni children who struggle with life-changing but non-life-threatening conditions in a country where the healthcare system is so overwhelmed by daily crises that little capacity remains for non-urgent cases.

As a child, I struggled with things that came easily to most others. I was a late talker, had trouble pronouncing words correctly and was uncomfortable with too many people around. In short, I had some symptoms of autism. But I was also very lucky. In Yemen, the Middle East’s poorest country, with the region’s lowest literacy rate and a United Nations Human Development Index near the bottom of the 189 countries measured, my parents had managed to beat the odds.

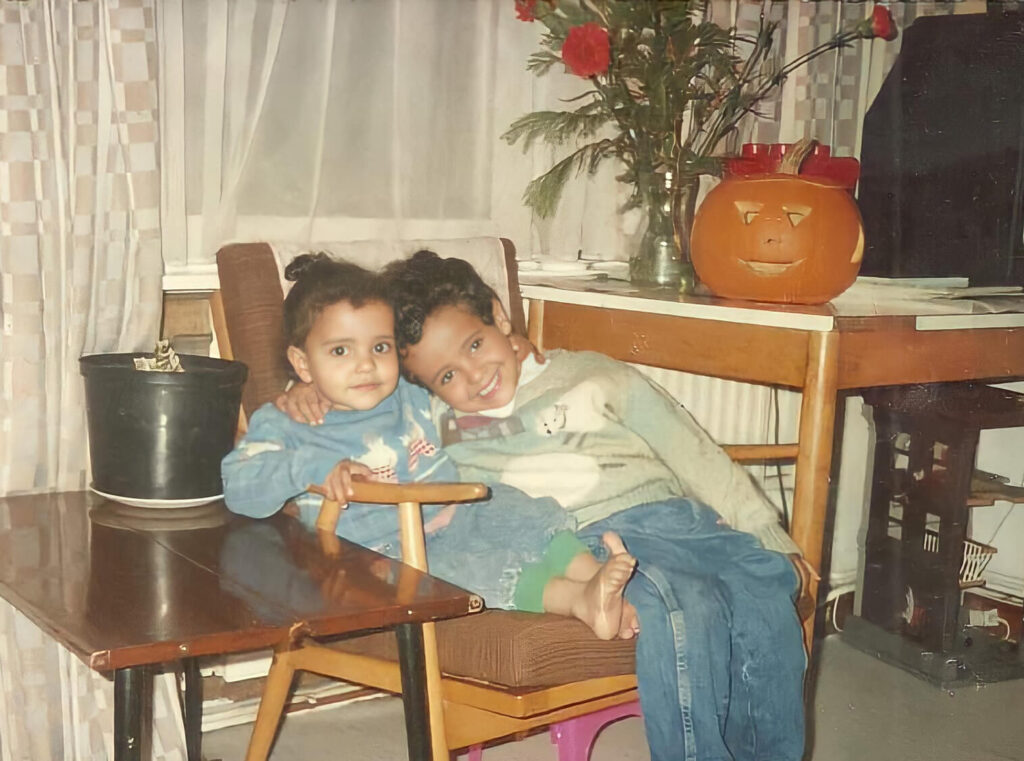

They had received an education and learned enough about child development to notice my symptoms at an early age. My father studied groundwater geology—a valued science in a country where sufficient supplies of potable water are always a concern. When he had the chance to continue his studies in Britain for post-graduate work , he took the family with him. I was two when we arrived in London in 1991. My mother, who had studied financial accounting in college, decided not to work and instead spent her time taking care of us and supporting my father on his educational journey. We stayed there five years, returning to Yemen when my father was offered a professorship at Sana’a University. Although he received several job offers from British universities, he felt the pull of home—where, he said, he could better serve his people.

Overcoming challenges

My symptoms of autism appeared early. I could not speak until I was 5. I remember always staying close to my mother, especially in public and on social occasions, which were my worst moments. I was terrified whenever I saw people begin to gather. I didn’t play football (soccer), nor did I play in the street like most kids do. But thanks to my mom and dad, with their support and their work with receptive school management and teachers, I was able to socialize more. My mother tells the story of an incident when I was in the third grade: one day I simply refused to attend class because the teacher was wearing a veil that covered her face. It frightened me, so they asked her to remove it for me. She did and I was very happy.

By the time I was 15, I had learned more about how to work with others. I went on to complete my studies and today hold a job that enables me to give back—to lend a hand to those struggling merely to survive in surroundings defined by war, hunger and want.

My father didn’t pressure me to do what other children were doing, but he treated me in a very special way. He didn’t make me feel different in a bad way. He made me feel different in a good way. For example, in 2000, when I was 11 years old and in the fifth grade, I was the only boy who had a computer. I spent most of my time drawing using the Paint app that still comes as a popular accessory with Microsoft Windows.

I got a cell phone when I was in the 7th grade in 2001, and my computer was connected to the Internet, so I could read and—especially important—meet people online in ways that I didn’t find frightening. Because I was at ease, I could create friendships. I wrote about these experiences in a brief article about myself—something all graduates of the College of Engineering were required to do. The article got noticed and was published by the official university magazine, along with a photo of drawings that I done during my adolescence. I recall my younger years as being a happy time, and I felt that my parents were proud of me. But not everyone in my extended family saw my upbringing that way.

In fact, most of them—including my uncles and aunts—disapproved of my upbringing and were critical of me. They told my parents they should send me out onto the street to mix with other children. My dad told them he knew how to raise me better than they did. His use of modern technology took my needs into account and connected me to the world in a way where I didn’t feel threatened.

A need for mental health services

In Yemen, the beliefs of my aunts and uncles remain the norm today. Autistic children are often forced to the margins of a society because they are viewed as “different.” And in a country where a child dies every 10 minutes from preventable causes, and where four out of every five people have no idea where they will find their next meal, uncommon life-changing—but non-life-threatening—conditions such as autism are largely overshadowed by the more pressing struggle for survival.

Although existing research suggests autism in Yemen has risen in recent years, and that as many as one in 50 children are autistic, awareness of the condition remains low. As a result, it remains one of many issues that receives too little attention—a fact that is sad yet understandable for a nation at war that is trying to deal with many public health threats, including cholera, diphtheria, the COVID-19 pandemic and child malnutrition.

There is also a critical lack of mental health services throughout the country, with existing services highly centralized at the secondary healthcare level—that is, at either psychiatric hospitals or in the psychiatric units of general hospitals. Primary healthcare centers are woefully unprepared to offer any type of mental health or psychosocial support (MHPSS). The results of a 2019 International Medical Corps assessment of 71 health facilities across the country found that only 10% had staff trained on the identification or treatment of mental health disorders. (The full report can be found on our website.)

A lack of understanding and awareness about autism often causes families—and entire communities—to keep autistic children hidden from view. This feeds discrimination and reduces the chances for understanding and social integration.

In my work for International Medical Corps, I’ve realized that my personal experience has made me acutely sensitive and receptive to people who may not be like those around them. It also has motivated me to become a strong advocate for all vulnerable groups, including the sick, the hungry and those who exist on the edge of survival. I am now considered a rare Yemeni male who champions women’s rights and strongly supports the rights of all people to live equally, regardless of their religion, race, social status or sexual orientation.

I know what it means to be different.

View next blog:

Fleeing the War in Yemen: One Family’s Odyssey

View previous blog:

On the Edge of Despair, an Aid Worker Knows There’s Only One Choice: Keep Going