Comfort Kollie remembers the day she was discharged from International Medical Corps’ Ebola Treatment Unit (ETU) like it was yesterday. “It was a Friday,” she says. “Someone came in [to the ETU and asked,] “Where is Comfort? You are Ebola-free today.’”

She had spent the past 17 days in the ETU fighting for her life. When she learned that her blood tested negative for the virus, on October 3, 2014, Comfort became the first female to emerge from International Medical Corps’ ETU in Bong County in north-central Liberia.

But after Comfort was home with husband, children, and grandchildren, her eyesight started to falter. A week later, she was unable to walk. “I couldn’t see,” Comfort says. “It was like a big cloud over my eyes. My bones and knees were hurting. I cried. I thought I would never see again.”

Comfort is one of many Ebola survivors who struggle with health complications as a result of the virus. Globally, there are more than 17,000 Ebola survivors, nearly all of whom live in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia, the three countries that were hit the hardest in the outbreak.

While Ebola transmission has slowed tremendously, emerging evidence suggests that Ebola can linger in parts of the body long after someone tests negative for the virus. This underscores that the health implications of the epidemic will not be over once all countries do not have any new cases for 42 days—twice the incubation period of the virus.

“There is still so much unknown about what happens to a survivor’s body once their blood test is negative and they are discharged from the ETU,” says Megan Vitek, a registered nurse and program coordinator for International Medical Corps Post-EVD Syndrome program. “Many survivors experience joint and body pain, psychosocial issues, and vision changes that have been categorized as Post-EVD Syndrome.”

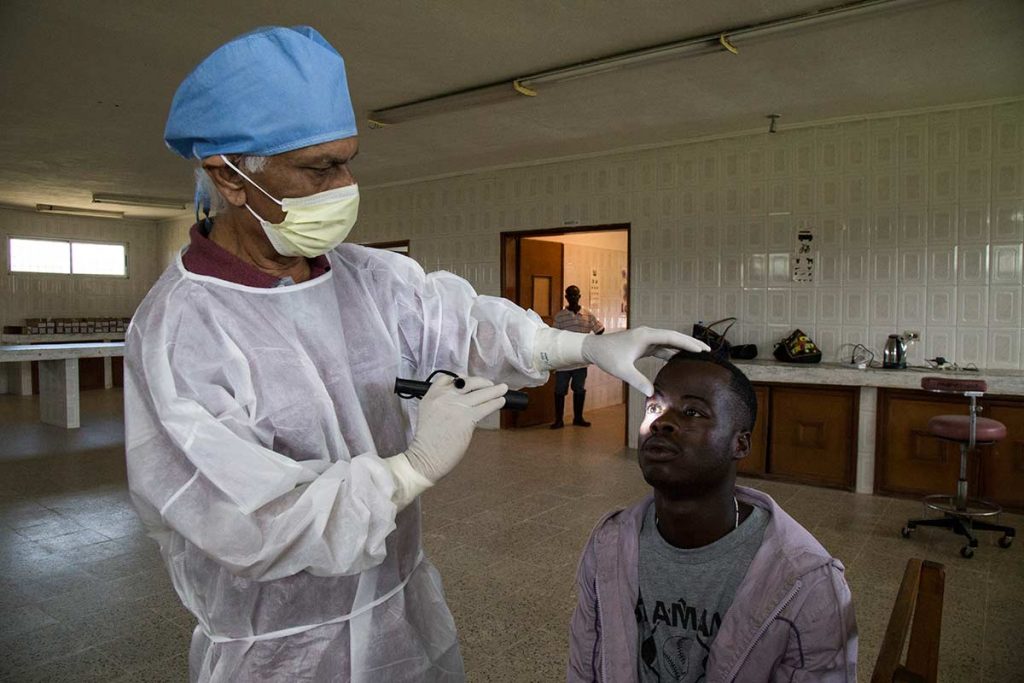

While the extent of these problems are still being researched, it has been documented that the virus can persist in semen, the inner eye, and even cerebral spinal fluid, leaving many questions unanswered as to where else it may remain and the risk to the survivor and future caregivers. “We are finding Ebola can cause inflammation of the iris,” says Dr. Narendra K. Sharma, an ophthalmologist based in Bong County with International Medical Corps. “This can cause lesions on the eye that can lead to blindness if it is left untreated.”

With an estimated 335 survivors in Bong and surrounding counties, International Medical Corps is working with Phebe Hospital to provide comprehensive services for survivors, including physical exams, ophthalmology services, physical therapy services, and psychosocial support. With International Medical Corps’ help, Phebe Hospital has become the only facility outside Monrovia able to care for people experiencing Post-EVD Syndrome.

In addition to providing direct medical care and supplies, Dr. Sharma, and his colleagues, Augustus Omalla, a physical therapist, and Dr. Husni, the program manager, are training clinicians in the hospital on how to assess and provide treatment for Post-EVD Syndrome symptoms.

“I believe everyone needs help,” says Hawa Varney, an ophthalmology nurse who has worked at Phebe Hospital for 11 years. She is one of two nurses receiving on-the-job training with Dr. Sharma. “I’ve been taking care of Post-EVD patients…Many of them lost their sight because of Ebola. They need someone to take care of them.”

However, without additional funding into 2016, survivors outside of Monrovia will have to pay for ophthalmology services, medicines, and lab tests, which will be restrictive for families already struggling to carve out a living. This also assumes that the medicines and supplies will be available to patients and staff, as supply chain management is a consistent issue for health care facilities in Liberia. Transport to the hospital can also be expensive—as much as $20 each way—a cost that does prevent people from making it to the hospital.

Providing training at one hospital is also not sufficient, as there are countless other clinicians and health care workers that will continue to engender fear and stigma towards survivors unless given the knowledge of how to safely and appropriately care for them.

“Liberia may have been declared Ebola-free, but the effects of the virus are wide-reaching for the health care system and survivors,” says Vitek. “Those who overcame this horrific virus should have access to treatment for whatever complications they encounter, but this requires a strengthening of the system. Training and support for health care facilities is critical so that we can equip local clinicians with the confidence and knowledge to provide care to Ebola survivors.”

Meanwhile, Comfort is back at work in the operating room at Phebe Hospital, where she worked for decades before Ebola struck. She still struggles with joint stiffness and pain and is waiting for glasses, but is now receiving eye care and physiotherapy services from Dr. Sharma and Mr. Omalla. “Because of the help, I can see clearly now,” Comfort says. “I can see with my eyes.”