Editor’s Note: International Medical Corps’ Yemen Blog presents a rare view of life on the ground in Yemen, chronicled by our first responders as they battle what is widely acknowledged as the world’s worst and largest humanitarian disasters—one fueled by poverty, hunger, disease and a seemingly endless war now in its seventh year, with no end in sight. Yemen’s misery has only gotten worse since COVID-19 arrived early last year and donor fatigue has reduced the funds needed to ease the suffering of innocent civilians.

The entry below is written by Dr. Nebras Khaled, our Health Program Manager in northern Yemen. She is based in Yemen’s capital, Sana’a, where she grew up, earned her medical degree and lived much of her life before joining International Medical Corps in 2014 as a mobile medical team leader. Her current responsibilities include helping to implement our healthcare, nutrition and water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) programs in three districts of Sana’a governorate that have been hit especially hard in recent years by the effects of war, crippling food shortages and high rates of disease.

Even for those living in countries where no humanitarian crisis exists, 2020 was a difficult year. But for the people of Yemen, it was little short of a nightmare. We always live with hope, but it’s very hard now, because so much of the hardship we faced last year has continued to stay with us into 2021. There is still no end in sight to the years of war that have destroyed so much of our healthcare system, crushed our economy and caused so much pain. In many areas, people now live on the brink of famine.

On top of this, we continue to struggle with two additional challenges that came to us last year. We are responding to the COVID 19 pandemic and despite widespread shortages, we have been able to provide personal protective equipment (PPE) and infection prevention and control items. In February alone, our teams in northern Yemen distributed nearly 29,000 such items to protect health workers dealing with the coronavirus. But for me, there is a bigger concern: cuts in the levels of humanitarian assistance that so many in northern Yemen depend on for their very survival. This is my biggest worry because I see its effects every day.

Although we have managed to keep our programs going without funding cuts, many other humanitarian relief groups have not been as fortunate. As the need for assistance grows, the deteriorating conditions and sense of heightened desperation is now part of our daily lives when our mobile medical teams visit the poorest villages of Al-Mukha district, just a few hours’ drive from the capital, Sana’a. We can see new families arriving, seeking shelter after being displaced by fighting from their homes elsewhere. It’s heart-wrenching, because we know that the kind of services humanitarian aid groups provide free of charge can make the difference between survival or death for those who need them most—services such as safe drinking water and treatment for child malnutrition.

Can we keep coming to these villages and provide what they need? If not, there is little alternative, because so few can afford to seek help elsewhere. Private-sector jobs have long since disappeared, and those fortunate enough to hold government positions have watched their incomes decline or disappear completely because the state has no money to pay them. To make matters worse, a fuel crisis has caused commodity prices to spike.

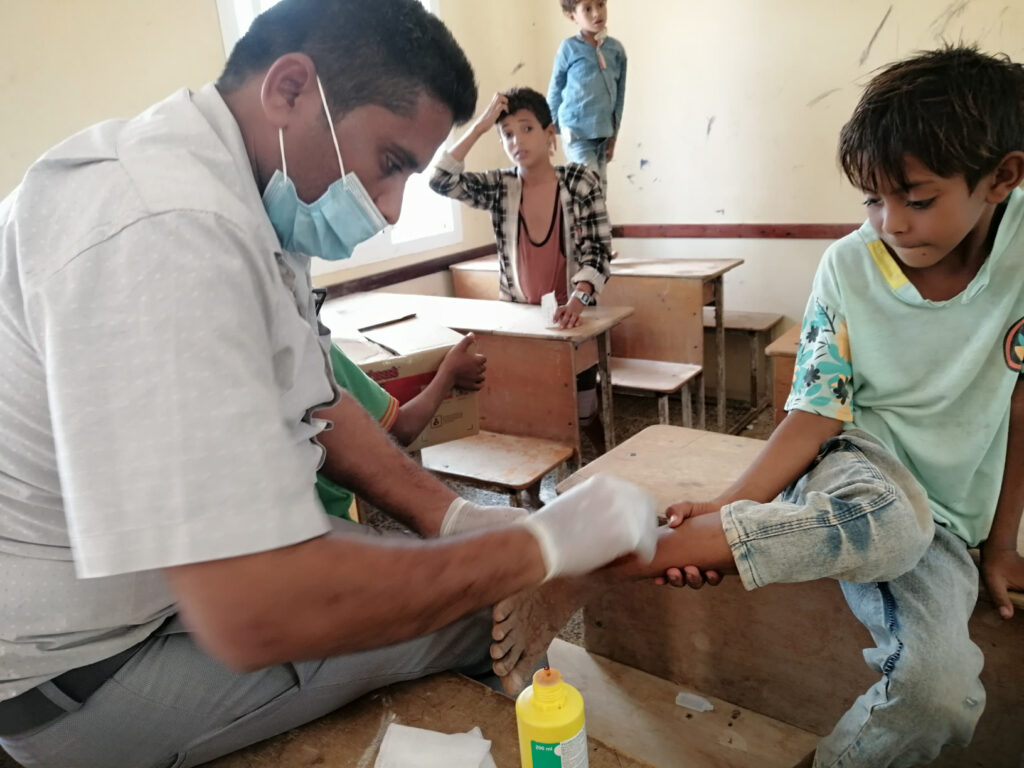

Amid all this, my team and I keep going—driving for long hours, moving from village to village to provide health and nutrition services to patients despite the many risks, including the presence of mines on the roads.

My spirits are lifted when I hear of children in these places whom we treated earlier and who have now recovered. One little boy simply stole my heart. His name is Shadad Mahmoud Hassan, from the village of dar al-Shujaa, who was just eight months old when I first learned of his case. It was clear Shadad was ill when his worried mother brought him to our mobile team. A standard measurement we use to determine nutrition levels of struggling children—measuring the mid-upper arm circumference, also known as MUAC—confirmed that Shadad was badly malnourished. We diagnosed him with several acute malnutrition and began treatment immediately. With his mother’s permission, our mobile team referred him to a Therapeutic Feeding Center two hours way for more intensive treatment. That care, combined with frequent weekly checks by our mobile team after he returned to his village, put Shadad on a path to recovery. Measurements taken at his latest check-up indicate that his body mass is now within the normal range for a healthy child his age.

The experience with Shadad changed me. It gave me new hope, new resolve. When he was first diagnosed, we could see conditions in the villages steadily getting worse, despite all our hard work and the risks we were taking. It all began to seem hopeless and I felt like giving up. But then the team sent me a photo of Shadad when they first met him, followed by a video sent during his recovery. Those images stayed with me. So have his struggle and the easing of his family’s worries. They were proof that we were making a difference.

I also draw strength from my team—the work that we’ve done and what we’ve all been through together to keep the services going. Now when I get discouraged, I think of my team and of Shadad, and remind myself that there are so many other children out there who also need our help. I know we have to keep going. I just pray we can keep the funding we have and that, someday, the war will end and we can do so much more.

View next blog:

Rebuilding Healthcare at Ground Zero of a Humanitarian Disaster

View previous blog:

A Beacon of Optimism and Resilience Shines in Dark Times